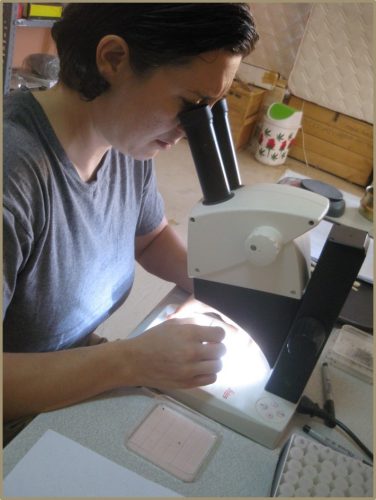

The identification of carbonized seeds requires looking at the plant remains under a stereoscopic microscope.

Archaeobotany is a sub-specialization within environmental archaeology that studies human interactions with plants in the past. There are several approaches to recovering plant remains in archaeological contexts, from the collection of microscopic fossil pollen, starches, and phytoliths (the silicate skeletons of plant cell structures), to the recovery of macroscopic charred seeds and wood charcoal. I conduct the latter, and study carbonized seed remains under a microscope to identify plant species. It turns out that if seeds are fired just right (crispy, but not ashy) they can preserve in the archaeological record for thousands, even tens of thousands, of years. Once I identify these seeds I’m able to assemble information on changes in agricultural production and plant consumption over time (e.g. Did the residents of Tel Akko cultivate different crops at different times?) and over space (e.g. Did the people of Tel Akko use different kinds of plants in different contexts on the site?). Plant remains can also help us reconstruct ancient landscapes; track the use of forage, graze and fodder for livestock; and ask questions about the kinds of social interactions that plants facilitate: e.g. Did food choices distinguish different ethnic or status groups? Did men and women conduct different kinds of agricultural labor? Did people in the past promote sustainable environmental practices, or engage in lifestyles that led to erosion, deforestation or pollution?

Charred seeds range in size from greater than 2 mm to as small as 200 microns.

When you think about it, most of the artifacts that archaeologists recover reflect only a very small proportion of the material culture that people utilized in the past. We find what endures: stone and mudbrick architecture, pottery, lithics (stone tools), bones, and metal items. But people in the past relied on and made so many other kinds of objects, a great deal of them from plant materials: e.g. timber architecture, wooden furniture and utensils, woven textiles, reed baskets, written documents, and, of course, plant foods. This continues to be the case today, even in the age of plastics. Look around you (and on you), and you will find materials made from plants that make your daily life possible. Archaeobotany is an attempt to recuperate these hard-to-find but oh-so-important physical elements of human life.

Still want to hear more about archaeobotany? Allow me to explain in person…

1 Comment