Moles: The Smallest Archaeologist?

The Moles-

There are plenty of issues that one must be prepared to encounter during an archaeological dig, though one I was not prepared for was the Palestinian Mole. At the Tel Akko dig, I encountered multiple mole tunnels during the excavation. The moles live underground and tunnel all throughout the various sections of the site, including the areas where I was assigned to work. These moles can cause multiple problems for archaeologists, due to the effects of their tunneling through the area.

Problems-

The tunnels go in multiple directions and loosen up soil, with the result that our tools can fall through them easily and cause an area that is being excavated to become less level. Leveling as neatly as possible is necessary for determining the origins of artifacts that can be discovered, so this can mix up our results. Tunneling also causes different artifacts to potentially fall to a lower level and get mixed up with other pieces that are unrelated. Sometimes, a stool that one of us may sit on while working in an area may fall into one of these holes. My supervisors described these effects as bioturbation: how living things move around and live in the soil and may impact a site’s integrity. Many insects and other rodents partake in this process at Tel Akko, though moles are some of the larger and most evident residents of the dig site.

Distribution-

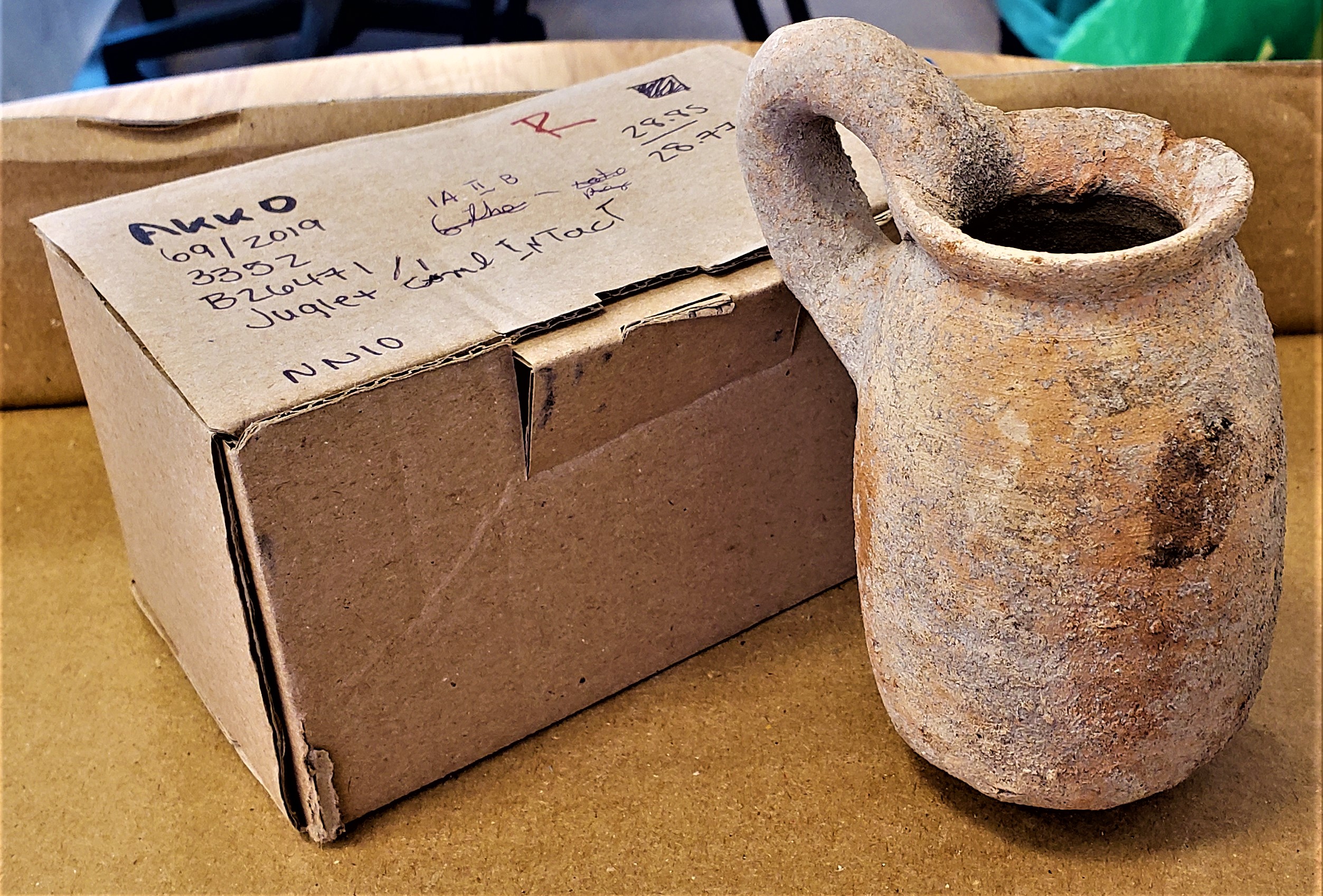

Tunnels can be seen across different areas, and there is evidence of mole tunneling in areas P 19, Q 19, and area Z, which are the places that I have been working. Moles have also been caught by staff members, as in the image of a mole included in this post. Moles are not seen often, but their trails are all over the place, whether intact and inside the artificial walls, the ground of different sections, or collapsed under our tools and stools.

Sometimes moles kick up dirt when these tunnels are damaged by our tools, in order to clean up their living space. This can explain why, when some of us turn around, there is a fresh pile of dirt that randomly appears when we aren’t looking. The moles are cute to look at and it is interesting how they impact the area, though the manner in which they kick up dirt and get artifacts mixed up can be problematic for people working in the field. That being said, whenever a fresh pile of dirt is kicked up or a mole comes out, everybody wants to see it and look at our fellow diggers.